|

|

Magic as Reassurance

by Craig Conley

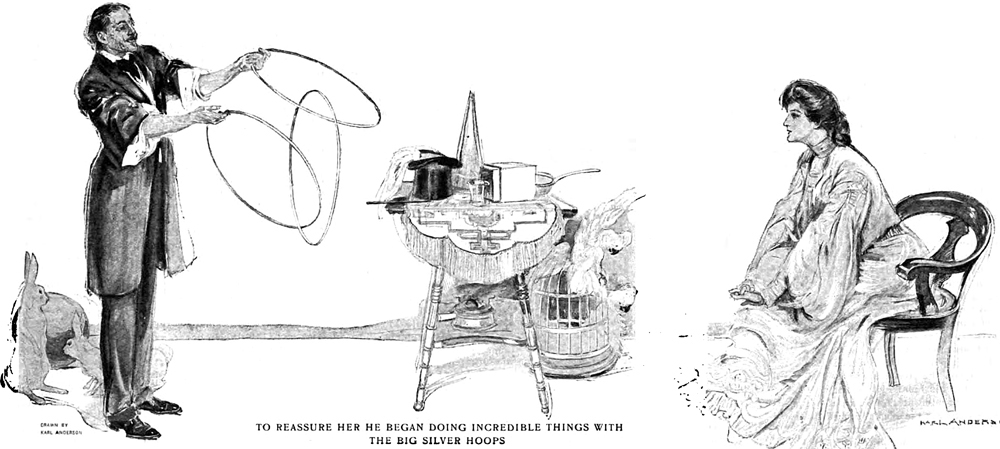

A magician begins “doing incredible things with big silver hoops” for no less a purpose that to REASSURE a spectator. (This we learn in an intriguing illustration in The Saturday Evening Post, Nov. 12, 1904.) We don’t typically associate reassurance — the restoration of confidence — to tricksters; we all know that a “confidence man” is ironically named.

Even so: “Around that word, reassure, a magic influence rests,” suggests Dr. Brose Horne in 1913. He says that to reassure someone “is simply scattering flowers on the path of life.“ It is the balm that heals the wounds. . . . Into every mind there creeps in doubts and in their weak moments they crave an influence that can come only from the fountain of ‘Reassurance’” (“The Magic Remedy–‘Reassure,’” National Drug Clerk, Vol. 1, p. 236).

Our first sense of magical reassurance might occur in early childhood, when a kiss on a splintered finger miraculously helps to soothe and calm. Interestingly, ‘soothe” traces its magical origin back to the Old English word for truth, as in the truth-telling “soothsayer.”

Beyond injury, some of the most common fears involve the Unknown, socializing, embarrassment, powerlessness, ridicule, rejection, failure, and death. How might a performance of stage magic symbolically offer reassurance to spectators? Most vital, of course, is not to deliberately feed fears, whether playfully or mischievously. The selection of a volunteer from the audience automatically sparks several fears simultaneously: there’s the looming Unknown, the inevitability of social interaction, the potential of embarrassment in front of a group, and surely a general feeling of powerlessness. Jeff McBride’s solution comes to mind, in which it’s not coercion but rather the proper resonance of a shaman’s bell that selects out a volunteer.

Another requisite for reassurance is genuineness. It is insincere to communicate reassurance in which the guarantee is worthless. Since death is an inevitable fact of life, can we genuinely dispel a fear of the grave? Jeff McBride tackled that question head on. He found a way to symbolically communicate reassurance about death via a mask routine in which layers of mortal flesh and bone are stripped away in a personal quest for indestructibility. The routine is reassuring on multiple levels: it demonstrates that the fear of death is not anyone’s alone but is in fact a shared experience; it demonstrates that soul searching (shown quite literally as a hunt for something beyond the flesh) might prove fruitful; it suggests (non-explicitly, even inexplicably) that there is yet more for humankind to discover about the nature of life and death. In a variety of ways, that mask routine wordlessly but profoundly soothes one of humanity’s greatest fears.

How does the demonstration of a mystery serve to put a spectator’s mind at rest? Consciousness itself is a mystery! When the Greek philosopher Heraclitus said “I went in search of myself,” he acknowledged that existence itself is an enigma to humankind. “A sharpened sensibility to the fullness of life restores mystery to a world grown otherwise too weary and wise in its skeptical and protective indifference to residuals of wonder. If we want the whole truth of human reality, we must first confront the mystery of life itself” (Lawrence Kimmel, “Literature, Mystery, and Truth,” 2004). Cue the magician.

|

|